What is wellness?

Throughout time and across cultures, the term “wellness” has been defined and applied in many ways. The National Wellness Institute encapsulates these interpretations by acknowledging that:

- Wellness is a conscious, self-directed, and evolving process of achieving one’s full potential.

- Wellness encompasses lifestyle, mental and spiritual well-being, and the environment.

- Wellness is positive, affirming, and contributes to living a long and healthy life.

- Wellness is multicultural and holistic, involving multiple dimensions.

“Wellness is functioning optimally within your current environment.”

Mindfully focusing on wellness in our lives builds resilience and enables us to thrive amidst life’s challenges. NWI promotes Six Dimensions of Wellness: Emotional, Physical, Intellectual, Occupational, Spiritual, and Social. Addressing all six dimensions of wellness helps individuals understand what it means to be holistically W.E.L.L. by focusing on their Whole Person, Environment, Lifestyle, and Learning.

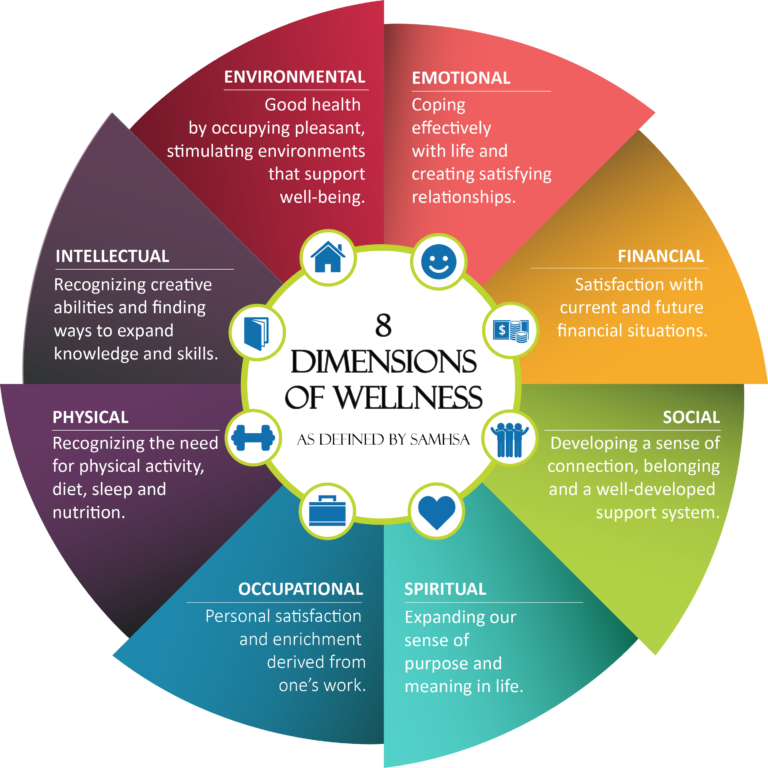

The eight dimensions of wellness are

- Emotional: coping effectively with life and expressing emotions

- Environmental: living in a healthy and safe environment

- Financial: managing money and planning for the future

- Intellectual: engaging in creative and stimulating activities

- Occupational: finding fulfillment and meaning in work

- Physical: maintaining a healthy body and lifestyle

- Social: developing positive and supportive relationships

- Spiritual: exploring values and beliefs

Go here to view video on eight dimensions of wellness