Forts In Pennsylvania

Forts In Pennsylvania

Carnahan’s Blockhouse – An important fortress during the latter part of the American Revolution, this blockhouse was built much earlier by Adam Carnahan. Carnahan, who was the son of Irish immigrants had come to Westmoreland County prior to the Revolutionary War and built the Carnahan Blockhouse located about 11 miles northeast of Hannahstown, and about two miles from the Kiskiminetas River. Adam enlisted in Captain Jack’s Company Cumberland County, Pennsylvania Militia, and was called into service by order of the council on January 1st, 1778. He was transferred to Captain John Hodge Company on August 1, 1780 and served until the war ended in 1782.

His blockhouse became a regular station during the war and a place of more importance after the garrison had been withdrawn from Fort Hand and placed along the line of the Allegheny River. Adam’s sons manned the blockhouse while their father was away. Adam’s son, John Carnahan, was killed by Indians just outside the blockhouse while trying to protect his family and others.

Fort Allen (1774-1783?) – In 1774, about 800 pioneer settlers lived in Hempfield Township, in Westmoreland County, Pennsylvania. Fearful of Indian attacks, they petitioned the colonial government for aid and protection. In response, Fort Allen was built, believed to have been named for Andrew Allen of the state’s then governing body, the Supreme Executive Council. Commanded by Colonel Christopher Truby, the post was also known as Truby’s Blockhouse. The post protected the Harrold’s and Brush Creek settlements during Dunmore’s War in 1774 and the American Revolution; however, it was never involved in an emergency. There is nothing left of the fort today but a stone monument. It is located on the grounds of St. John’s Harrold United Church of Christ at the corner of St. John’s Church Road and Baltzer Meyer Pike, which is about 150 yards north of where the fort was located.

Fort Antes (1777-1778) – The home of Colonel John Henry Antes, a member of the Pennsylvania Militia, this fort was surrounded by a stockade. Built in about 1777, it was situated on the east side of Antes Creek, overlooking and on the left bank of the West Branch Susquehanna River on a plateau in Nippenose Township in western Lycoming County. See full article HERE

Fort Augusta (1756-1794) – A stronghold in the upper Susquehanna Valley from the French and Indian War to the close of the American Revolution, Fort Augusta was built on the site of Shamokin, the largest Indian town and trading center in Pennsylvania. Built with upright logs facing the river, and lengthwise in the rear, and was about two hundred feet square. The main wall of the fort was faced about half its height by a dry ditch. A triangular bastion in each corner permitted a crossfire that covered the entire extent of the wall. The main structure of the fort enclosed officers’ and soldiers’ quarters, a magazine, and a well, the last two of which are still preserved. it is said to have had sixteen mounted cannons.

On July 8, 1736 Shamokin was described as having eight huts beside the Susquehanna River with scattered settlements extending over seven to eight hundred acres between the river and the mountain. Terrified of vengeful white soldiers, the Indians burned their homes and abandoned the site in the days leading up to the French and Indian War. Within days, the British began construction of the fort in defense against the raids of the French and Indians from the upper Allegheny region.

American Revolution, Fort Augusta was the military headquarters of the American forces in the upper Susquehanna Valley. The activities of the Northumberland County Militia, the sending of troops to serve in Washington’s army, and the support and protection of smaller posts throughout the valley were all directed from the fort, where Colonel Samuel Hunter, the last commandant, resided.

During its use, Fort Augusta, with its strength and strategic location, was never forced to endure a siege. After the War, Colonel Hunter was allowed to retain the Commandant’s Quarters as his property. Over the years, it gradually deteriorated, but his descendants continued to live there until 1848, when the log house burned. Four years later, Hunter’s grandson, Captain Samuel Hunter, built another home. Both men are buried in the Hunter-Grant Cemetery across the street.

In 1930, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania purchased the land on which the well and magazine are located, and, in 1931, acquired the larger tract, which included The Hunter House. The Fort Augusta property is now the headquarters of the Northumberland County Historical Society in Sunbury, Pennsylvania.

Fort Bedford, PennsylvaniaFort Bedford (1758-1770) – A French and Indian Warr-era British military fortification, this post was located in what was first called Raystown, Pennsylvania which was first settled in 1751. See full article HERE.

Fort Boone (1777-1779) – Located near Milton, Pennsylvania, this fortress was situated about one mile north of Milton near the mouth of the Muddy Run River. A gristmill, it was operated by Captain Hawkins Boone, who was not known to have been related to the more famous Daniel Boone. During the American Revolution, three locals, including Captain Hawkins Boone, Captain John Brady, and Captain Samuel Daugherty were mustered out of the 12th regiment and sent, at the request of the people of the West Branch of the Susquehanna River Valley, to lead their defense. Captain Boone stockaded his mill, assisted by the two other captains and his neighbors and troops who were defending it. A large, hardy, brave, generous man, he appears to have been highly respected by those knowing him. When the three captains at Fort Boone heard about a large attack on nearby Fort Freeland, they and their troops rushed to provide aid and all three were killed.

This area was extremely volatile during the Revolutionary War because it was at the farthest edge of the frontier, where there were frequent attacks on the colonists by the British army, American loyalists and Native American tribes aligned with the British. Beyond this point, there was no colonial government and no protection. However, there were several other small forts in this area, most notably, Fort Freeland. In late June, 1779 after repeated attacks by the British, a number of colonial families moved from their homes to live behind the walls of Fort Freeland. Although there were rumblings of a pending attack, the colonists were completely unprepared when more than 300 British soldiers and supporters stormed the Fort Freeland early on the morning of July 28, 1779. With all the able-bodied men already off to war, there were only 21 boys and old men to defend the fort. Seeing the hopelessness of their situation, the colonists soon negotiated a surrender. News of the attack reached Captains Hawkins Boone, John Brady, and Samuel Daughterty who were leading the defense at nearby Fort Boone. A relief party rushed into defend the Fort Freeland, not knowing that it had already surrendered. The battle that followed was one of the bloodiest of the American Revolution and pivotal because the fall of Fort Freeland left the colonial American frontier defenseless. All three captains were killed. Later, another mill called the Kemmerer Mill was built at the same site as Boone’s Mill. It was located about about midway between Milton and Watsontown.

Fort Bosley (1777-1883?) – Located in the forks of the Chillisquaqua River at Washingtonville, Pennsylvania, a gristmill was built in in about 1773 by a Mr. Bosley, who moved here from Maryland a few years before the American Revolution. The Chillisquaque Valley and its surroundings are among the most beautiful in Pennsylvania. This great scope of fine arable lands attracted settlers early and Bosley’s Mills became a necessity. It soon became widely known; roads and paths led to it as a central point, and on the Indians becoming troublesome and the mill stockaded in about 1777. It became a haven of refuge at which the wives and families could be placed in safety at alarms, while the husbands and fathers scouted for intelligence of the enemy or defended the fort. It was soon recognized by the military authorities as post of importance and was garrisoned by troops. After the fall of Fort Freeland in July, 1779, the fort became even more important, holding the forks of the Chillisquaqua River and defending the stream below it. Though the fort was never heavily garrisoned, estimated to have had only 20 men at most, it was strong, and there are no records of any attacks. Somewhere, along the line Bosley’s Mill was replaced by a more modern mill. It was located just outside of the town of Washingtonville, somewhere near Muddy Run and the Chillisquaque Creek meet.

Fort Brady (1777-1779) – The dwelling house of Captain John Brady, this “fort” was located at Muncy, in Lycoming County, Pennsylvania. Captain John Brady had been a captain in the Scotch-Irish and German forces west of the Alleghenies under Colonel Henry Bouquet in his expeditions during the French and Indian War and had received a grant of land with the other officers in payment for his services. In the American Revolution, he was a captain in the 12th Pennsylvania Regiment and was wounded at the battle of the Brandywine. His son, John, a lad of 15 years, stood in the ranks with a rifle and was also wounded. Sam, his eldest son, was in another division and assisted to make the record of Parr’s and Morgan’s riflemen world famous. The area of the West Branch of the Susquehanna River, in its great zeal for the cause of the colonist, had almost denuded itself of fighting men for the Continental Army. Consequently, on the breaking out of Indian hostilities a cry for help went up from these sparsely settled frontiers. General George Washington recognized the necessity, but was unable to relieve them. He did, however, muster out several officers to organize a defense of the area.

Captain John Brady was one of the officers mustered out and soon after the Battle of Brandywine, he came home and in the fall of 1777, stockaded Fort Brady. He did this by by digging a trench about four feet deep and setting logs side by side, filling in with earth and ramming the logs down solid to hold the palisade in place. They were about twelve 12 feet high from the ground, with smaller timbers running transversely at the top, to which they were pinned, making a solid wall. Captain Brady’s house was a large one for the time.

Fort Brady quickly became a place of refuge to the families within reach in times of peril and continued so until after the death of the valiant captain and the driving off of the inhabitants. On April 11, 1779, taking a wagon and a guard, he made a trip up the river to Wallis to procure supplies. Brady was riding a fine mare some distance behind the wagon. A young local man by the name of Peter Smith, was walking along with him. After securing a quantity of provisions, the two started their return in the afternoon. When within a short distance of his home, Brady suggested to Smith the propriety of his taking a different route from the one the wagon had gone, as it was shorter.

They traveled together until they came to a small stream of water called Wolf Run, where the other road came in. Brady observed: This would be a good place for Indians to hide; Smith replied in the affirmative, when three rifles cracked and Brady fell from his horse dead. As his frightened mare was about to run past Smith, he caught her by the bridle and, springing on her back, was carried to Brady’s Fort in a few minutes. The report of the rifles was plainly heard at the fort and caused great alarm. Several persons rushed out, Mrs. Brady among them, and, seeing Smith coming at full speed, anxiously inquired where Captain Brady was. It is related that Smith, in a high state of excitement, replied: “In Heaven or hell, or on his way to Tioga,” meaning he was either killed or a prisoner by the Indians. The Indians, in their haste did not scalp him, nor plunder him of his gold watch, some money and his commission, which he carried in a green bag suspended from his neck. His body was brought to the fort and soon after interred in the Muncy burying ground, some four miles from his home.

In May, Buffalo Valley was overrun by the enemy and most of the people left. On July 8, 1779, Smith’s Mill, at the mouth of the White Deer Creek was burned, and on the 17th, Muncy Valley was destroyed. Starrett’s Mills and all the principal houses in Muncy Township were also burned, along with Forts Muncy, Brady and Freeland, and Sunbury. The site of Fort Brady is within the town of Muncy today.

Fort Deshler, PennsylvaniaFort Deshler (1760-1763) – This French and Indian War era frontier fort was built by Adam Deshler, who was employed to furnish provisions for provincial forces. The fortified stone blockhouse, was about 40 feet long and 30 feet wide, with walls that were 2 1/2 thick. It also served as Deshler’s home. Adjoining the building was a large wooden building, suitable as barracks for twenty soldiers and for storing military supplies. However, there is o evidence that the fort was ever garrisoned, serving instead refuge and rendezvous for settlers of the region. Located near the present-day intersection of Pennsylvania Route 145 and Chestnut Street, between Egypt and Coplay, it remained in the Deshler family until 1899, at which time the building and its remaining 151 acres, were sold to the Coplay Cement Company. Never preserved, it deteriorated until it finally collapsed in about 1940. Today, all that is left is a historic marker.

Fort Dickinson/Durkee (1769-1784) – In 1769, Major John Durkee and his men erected Fort Durkee on the eastern bank of the Susquehanna River at what is present-day Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. The fort included four small blockhouses and was armed with four guns. In the beginning, it was manned by about 100 men. The fort changed hands several times during what was known as the Yankee-Pennamite War, a conflict between Pennsylvania and Connecticut over the ownership of the Wyoming Valley. At the conclusion of the American Revolution, Congress was asked to decide on the legal owner and on December 30, 1782 adopted the Decree of Trenton, which granted the land to Pennsylvania. The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania then ruled that the Connecticut Yankees were not citizens of the Commonwealth, could not vote, and were to give up their property claims. Fort Durkee was renamed Fort Dickinson in 1783. It was destroyed by Connecticut Yankees in November, 1784 during the Second Yankee-Pennamite War.

Fort Duquesne – Established by the French in 1754, this post was situated at the junction where the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers come together to form the Ohio River, in what is now downtown Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. See full article HERE.

Fort Freeland, PennsylvaniaFort Freeland (1778-1779) – Situated on Warrior Run Creek, about four miles east of Watsontown, Pennsylvania, the site first held a mill built by Jacob Freeland in about 1774. In 1772, Jacob Freeland and several other men from Essex County, New Jersey, cut their way through the dense woods and settled with their families in in the area. More families soon followed and they lived on friendly terms with the Indians until 1777, when tribes began to rebel. At this time, many of the settlers removed their families; but, in the fall of 1778, the men returned and stockaded the home of Jacob Freeland. The pickets enclosed Freeland’s large two-story log house and enclosed a half acre of ground. That winter, several families moved into the fort.

In the spring of 1779, the men planted corn and were occasionally surprised with the Indians, but, nothing serious occurred until the July 21, 1779 when some of the men working in the field were attacked by a party of Indians in the morning. Isaac Vincent, Elias Freeland and Jacob Freeland, Jr., were killed and Benjamin Vincent and Michael Freeland were taken prisoners. Ten year-old Benjamin Vincent hid in a furrow, but, he was also captured.

Nothing again occurred until the morning of the July 29th. At about day-break, as Jacob Freeland, Sr. was going out of the gate he was shot and fell inside of the gate. The fort was surrounded by about 100 British troops and 300 Indians, commanded by Captain McDonald. In the Battle of Fort Freeland, there were only about 21 men in the fort, who had little ammunition. At about nine o’clock a.m. there was a flag of truce raised, and negotiations began. By noon, an agreement had been made that all who were able to bear arms would be taken as prisoners, and the old men, women and children set free, and the fort given up to plunder. After the surrender of Fort Freeland, Captains Hawkins Boone and Samuel Daugherty arrived with 30 men; supposing the fort was still holding out. As they made a dash across Warrior Run, they were surrounded. Boone and Daugherty, with nearly half their force were killed. The remainder broke through their enemies and escaped. Thirteen scalps of this party were brought into the fort in a handkerchief. Soon afterwards, the fort was set

on fire and burned down.

The effect of the fall of Fort Freeland and the desertion of Fort Boone was disastrous to the region left Fort Augusta uncovered to the inroads of the enemy. In the meantime, Colonel Samuel Hunter, commanding Fort Augusta, had few men and finally in November, a German Battalion of about 120 men was sent to him. After securing Fort Augusta, he ordered his men to build Fort Rice and Fort Swartz and garrisoned both.

Years later, the Hower-Slote House was built on the site of Fort Freeland in 1829 by James Slote. Built in the Federal style, it was the center of a working farm for more than 125 years. It still stands today.

Fort Gaddis (1764?-1783?) – This fort was built by Thomas Gaddis, who was in charge of the defense of the region, in about 1764, on the Catawba Trail, an important north-south route that extended from New York to Tennessee and passed through Uniontown, Pennsylvania and Morgantown, West Virginia. It was utilized as a place of refuge from the hostile Indians, as well as a site for community meetings. Gaddis was later a colonel in the Pennsylvania Continental Line during the American Revolution. The 1-1/2-story, 1-room log structure measures 26 feet long and 20 feet wide. During the Whiskey Rebellion a Liberty Pole was erected at the house during a rally in support of the rebel cause. The choice of this site for a political demonstration indicates its importance as a focal point for community expression. In the 19th century the Catawba Trail became locally known as the Morgantown Road. It is now Old U.S. Route 119. The building was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1974 as the “Thomas Gaddis Homestead”. Today, Fort Gaddis is the oldest known building in Fayette County, Pennsylvania and the second oldest log cabin in Western Pennsylvania. It is located about 300 yards east of old U.S. Route 119, near the Route 857 intersection in South Union Township, Fayette County, Pennsylvania.

Fort Granville (1755-1756) – Situated on the west bank of the Juniata River near present-day Lewistown, Pennsylvania, this fort, with blockhouses at each corner, was built in the winter of 1755-56 under the supervision of George Croghan. It was named after John Carteret, the Earl of Granville. Each side was about 100 feet long. The French and Indians challenged the fort on July 22, 1756 and when Captain Edward Ward refused their surrender demands, the French and Indians split-up and plundered the farms of a Mr. Baskin and then Hugh Carroll — making them prisoners. On July 30, 1756 Captain Ward went with a majority of his men to help protect harvesters in Shearman’s Valley. Observing his departure, about 100 French and Indians took advantage of the depleted defense and overran the fort — burning it to the ground. They were led by Louis Coulon de Villiers and Captain Jacobs (Tewea, a Delaware war chief. Lieutenant Edward Armstrong, who had been left in charge during Captain Ward’s absence, was killed during the defense of the fort. When the fort fell, a man named Turner accepted the surrender demand offering passage for the survivors. After the capitulation, the 22 soldiers, three women and seven children were loaded-up and taken to Kittanning. Turner was scalped alive and burned at the stake at Kittanning. The fall of Fort Granville confirmed the vulnerability of the string of forts on the western frontier of Pennsylvania.

Fort Halifax (1756-1757) – Located along the Susquehanna River near the present-day city of Halifax, this was temporary stronghold in the French and Indian War. A subpost of Fort Augusta, the fort was erected by Colonel William Clapham, under orders from Gouverneur Morris. The 160 feet square log stockade with four bastions was guarded by a garrison of the Pennsylvania Colonial Militia. It was dismantled in 1757 and its garrison was moved to Fort Hunter. In 1926 a stone monument was erected to designate the site of the fort. It is located along PA Route 147 north of Halifax along Armstrong Creek. The area of the former fort is now part of the Halifax Township Park and Conservation Area.

Fort Hand (1777-1779) – The only fort erected in Westmoreland County by Continental Congress, this fort was a blockhouse surrounded by a stockade with wall guns that covered about an acre of land. Built between 1777 and 1779, it was named for General Edward Hand. It was used until 1791 as a refuge against Indian attack. On April 26, 1779, Fort Hand was attacked by about 100 Indians against an independent company of some 17 men commanded by Captain Samuel Moorhead. The fight ended around noon of the following day when the Indians apparently decided the fort was not worth the effort. One of the three men in the fort wounded in the battle, later died. The women in the fort supported the fight by becoming ammo carriers and seeing to the nourishment of the militia. The Indians torched a few buildings and went to enclosures and killed all the cows and sheep. While the fight was going on at Fort Hand, other Indians attacked Fort Ligonier where they were also unsuccessful. The site was located at 285 Pine Run Church Road, (Kunkle Park), off PA 66 south of Apollo, Pennsylvania

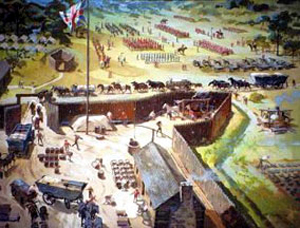

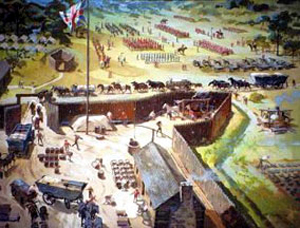

Fort Hanna’s Town todayFort Hanna’s Town (1774-1786?) Hanna’s Town was the first county seat of Westmoreland County and the first English court west of the Allegheny Mountains. Founded in 1773, it was named for its founder Robert Hanna. At the time of Dunmore’s War in 1774, Arthur St. Clair directed that a fort be built at Hanna’s Town in preparation for possible Indian attacks. The town became an oasis for travelers, settlers, and those seeking justice and order in the often chaotic environment of the western Pennsylvania colonial frontier. The fort took on added significance during the American Revolution after the abandonment of the fort at Kittanning. It became an important center for the recruitment of militia for the western campaigns against the British in Detroit and their Native Americans allies. In one of the final battles of the war, Hanna’s Town was attacked and burned on July 13, 1782 by a raiding party of Indians and their British allies. The town never recovered, and the county seat was moved to Greensburg in 1786. The old town was then converted to farmland. In 1969, the Westmoreland County Historical Society led an investigation of the site and found the exact footprint of the old fort. Today, it has been reconstructed along with several of the town buildings, including the Hanna Tavern/Courthouse, three vintage late 18th century log houses, the reconstructed Revolutionary era fort, blockhouse and a wagon shed. It is located about three miles north of Greensburg, just off Route 119

Green Man

Green Man

Forts In Pennsylvania

Forts In Pennsylvania What started as a tax in 1791 led to the Western Insurrection, or better known as the Whiskey Rebellion of 1794, when protestors used violence and intimidation to prevent federal officials from collecting.

What started as a tax in 1791 led to the Western Insurrection, or better known as the Whiskey Rebellion of 1794, when protestors used violence and intimidation to prevent federal officials from collecting.